Deep in the heart of Central Africa, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) holds vast reserves of minerals that power the modern world. Beneath its soil lie critical resources like cobalt and copper—essential components of smartphones, electric vehicles, and countless other technologies. Yet, while the world benefits from these minerals, the people of the DRC remain locked in a cycle of poverty, exploitation, and suffering. Nowhere is this crisis more visible than in the thousands of children who toil in the country’s mines, sacrificing their education, health, and future for a pittance.

The DRC, a nation roughly the size of Western Europe, is one of the poorest countries on Earth, despite its natural wealth. In 2024, approximately 73.5% of its population lived on less than $2.15 per day (World Bank, 2024).[1] This dire economic situation fuels the continued use of child labor in mining, where young boys and girls work in hazardous conditions to help their families survive. The consequence? A lost generation of children deprived of education, condemned to a life of labor with little hope for upward mobility.

The Persistent Problem of Child Labor in Mining

The mining sector dominates the Congolese economy, contributing over 70% of the country’s economic growth. However, it is also one of the worst offenders when it comes to child labor. In provinces like Katanga and Lualaba, thousands of children—some as young as six—work long hours mining cobalt, often using their bare hands to dig through toxic soil. These children are exposed to dangerous chemicals, suffer from respiratory illnesses, and endure extreme physical strain.

Many are forced to drop out of school, while others try to juggle both mining and education, leading to chronic absenteeism and poor academic performance. Even those who momentarily escape the mines often return due to financial pressures, trapped in a cycle known as child labor recidivism. The global demand for cobalt ensures that there is always work in the mines—but for these children, it comes at the cost of their future.

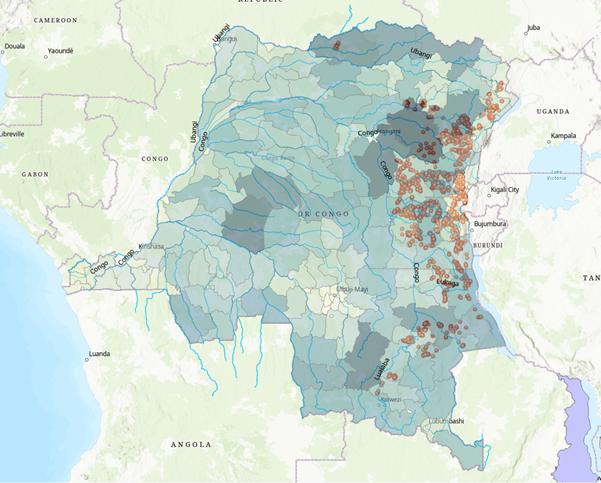

Figure 1. Map of DRC shows administrative subdivisions. Cobalt mines (artisanal and industrial) are shown in the eastern part of the country.

Absenteeism and Its Impact on Educational Achievement

The Human Capital Index (HCI) for the DRC stands at 0.37, meaning that a Congolese child born today will achieve only 37% of their full productivity potential due to poor education and health outcomes. This is among the lowest in the world, even compared to other low-income countries.[2]

Consider the sobering education statistics:[3]

- Expected Years of Schooling: 9.1 years—but when adjusted for learning, this equates to just 4.5 years.

- Harmonized Test Scores: Congolese students score an average of 310 on a scale where 300 represents minimal learning and 625 indicates advanced learning.

- Primary School Completion Rate: 75%—one of the lowest in Sub-Saharan Africa.

- Learning Poverty: A staggering 97% of 10-year-olds in the DRC cannot read and understand a simple text (World Bank, 2024).

Mining further exacerbates these issues. Children who work in the mines often miss school due to sheer exhaustion, illness, and financial hardship. Many parents, struggling to afford school fees and materials, prioritize immediate financial survival over long-term education. Even those who do attend school face overcrowded classrooms, underpaid teachers, and a lack of basic learning materials.

The Economic Trap: Why Families Remain in Poverty

Despite their crucial role in one of the world’s most profitable industries, child miners and their families remain trapped in extreme poverty. Without an education, child miners grow into adults who are stuck in low-wage, high-risk jobs, perpetuating the cycle of poverty. Chronic illnesses from mining exposure increase medical expenses and shorten life expectancy, placing further strain on family resources. When families rely on child labor for survival, they fail to invest in education, ensuring that the next generation faces the same economic struggles, resulting in intergenerational poverty.

The Double Burden on Women and Girls

Girls in mining communities face an even steeper uphill battle. Only 16.8% of Congolese women complete secondary school, with early marriage and gender-based violence limiting their opportunities. Those working in the mines are at high risk of sexual exploitation, trafficking, and abuse. The lack of education for girls not only perpetuates gender inequality but also contributes to higher fertility rates, lower lifetime earnings, and reduced economic independence.

The Role of Global Corporations in Perpetuating Child Labor

Despite corporate pledges to source minerals responsibly, the reality is grim. Tech and automotive giants rely heavily on Congolese cobalt, and supply chain transparency remains weak. While some companies have introduced “conflict-free” sourcing initiatives, many continue to profit from a system that exploits child labor. Without stricter international regulations and supply chain oversight, child miners will remain the backbone of the cobalt industry.

Breaking the Cycle: Solutions for Sustainable Change

Addressing child labor and absenteeism in the DRC requires bold action on multiple fronts, noted by the US Department of Labor’s COTECCO project (Combatting Child Labor in the Cobalt Supply Chain) of the Congo’s Cobalt Industry.[4]

Stronger Legal Enforcement: The Congolese government must enforce child labor laws and hold corporations accountable for ethical sourcing.

- Educational Investment: Free schooling, improved infrastructure, and school feeding programs can reduce barriers to education.

- Alternative Livelihoods for Families: Microfinance initiatives and vocational training can provide sustainable alternatives to mining.

- Corporate Accountability: Tech companies and auto manufacturers must conduct stricter due diligence and refuse to buy minerals linked to child labor.

- Global Consumer Awareness: Ethical consumer campaigns can push companies to commit to child labor-free supply chains.

Conclusion: The Future of DRC’s Children

The plight of child miners in the DRC is a humanitarian crisis that cannot be ignored. Every day, thousands of children risk their health and futures to extract minerals that power the modern world. The global economy has a moral obligation to ensure that the products we use are not built on the suffering of the world’s most vulnerable.

With the DRC’s Human Capital Index at 0.37, it is clear that the nation is failing to invest in its youth. Without urgent reforms, another generation will be lost to the mines—trapped in a cycle of poverty, deprivation, and unfulfilled promise.

Now is the time for action. Governments, corporations, and consumers alike must take a stand against child labor in mining. The future of an entire generation depends on it.

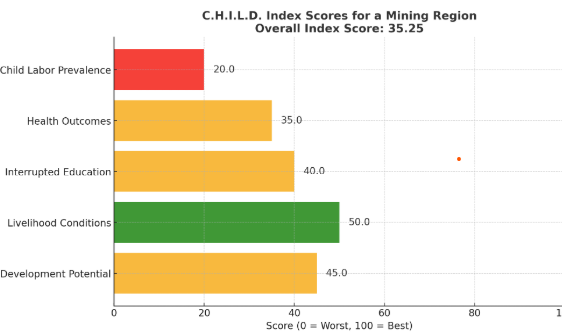

Floodlight has developed an index called, CHILD, Children’s Human Capital, Indicators of Labor, and Development. This index is a composite metric designed to evaluate the impact of mining on child welfare and education DRC. This index will combine quantitative and qualitative indicators to measure how child labor in mining affects health, education, economic conditions, and long-term human capital development. visualized for a hypothetical mining region in the DRC. Each component reflects child labor prevalence, health outcomes, education interruption, livelihood conditions, and long-term development potential. Lower scores indicate greater severity of issues, and the overall index score (weighted average) provides a single benchmark for assessing child welfare in mining areas. The overall score of 35.25 shows that there is much room for improvement in the various components. Floodlight can provide specific recommendations to address these issues.

Figure 2: Floodlight index CHILD to measure the health and well being of children using a hypothetical example.

References:

Banza Lubaba Nkulu, C., Casas, L., Haufroid, V., De Putter, T., Saenen, N. D., Kayembe-Kitenge, T., … & Nemery, B. (2018). Sustainability of artisanal mining of cobalt in DR Congo. Nature sustainability, 1(9), 495-504.

Bowman, A., Frederiksen, T., Bryceson, D. F., Childs, J., Gilberthorpe, E., & Newman, S. (2021). Mining in Africa after the supercycle: New directions and geographies. Area, 53(4), 647-658.

Kara, S. (2023). Cobalt red: How the blood of the Congo powers our lives. St. Martin’s Press.

Smith, J. H. (2021). The Eyes of the World: Mining the Digital Age in the Eastern DR Congo. University of Chicago Press.

Wells, K. (2021). Childhood in a global perspective. John Wiley & Sons.

[1] https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/drc/overview

[2] https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/7c9b64c34a8833378194a026ebe4e247-0140022022/related/HCI-AM22-COD.pdf

[3] https://www.unicef.org/drcongo/en/what-we-do/education

[4] https://www.dol.gov/agencies/ilab/combatting-child-labor-democratic-republic-congos-cobalt-industry-cotecco