Key Takeaways

- Many of the factors that led to Hurricane Lee intensifying were observable prior to the storm becoming a category 5 hurricane, mainly ocean temperatures and a lack of wind shear.

- Floodlight’s climate intelligence solutions offer the ability to quantify and forecast climate related risks like storm risk and associated financial value at risk, as well as monitor impacts related to such risks, like GHG emissions. For more information, please visit our product page or feel free to reach out directly.

Both New England and Atlantic Canada are carefully watching the tropics this week. As Hurricane Lee looms thousands of miles away in the lower latitudes, forecasters are piecing together information on where it goes next. There are many complex atmospheric features relevant to Lee’s path which will determine where and if the powerful storm makes landfall. While the answer to this intricate meteorological puzzle will be resolved soon, the story of how Lee came to be is already written.

Hurricane Lee was initially a tropical wave coming off the coast of Africa at the beginning of September. Many, though not all, hurricanes start off as tropical waves. A tropical wave is simply an unorganized area of low pressure that is powerful enough to consolidate into a tropical depression, storm, or, potentially, hurricane. The evolving conditions surrounding Lee make its timeline especially notable. On September 5th, Lee became a tropical storm. On the following day, a late-night press release from the National Hurricane Center (NHC) set the maximum intensity of Lee at 70 knots (80 mph), making it a category 1 hurricane. 24 hours later, meteorologists gauged Lee’s intensity at 140 knots (160 mph), 80 mph more than the previous day, marking the storm as 2023’s first category 5 hurricane.

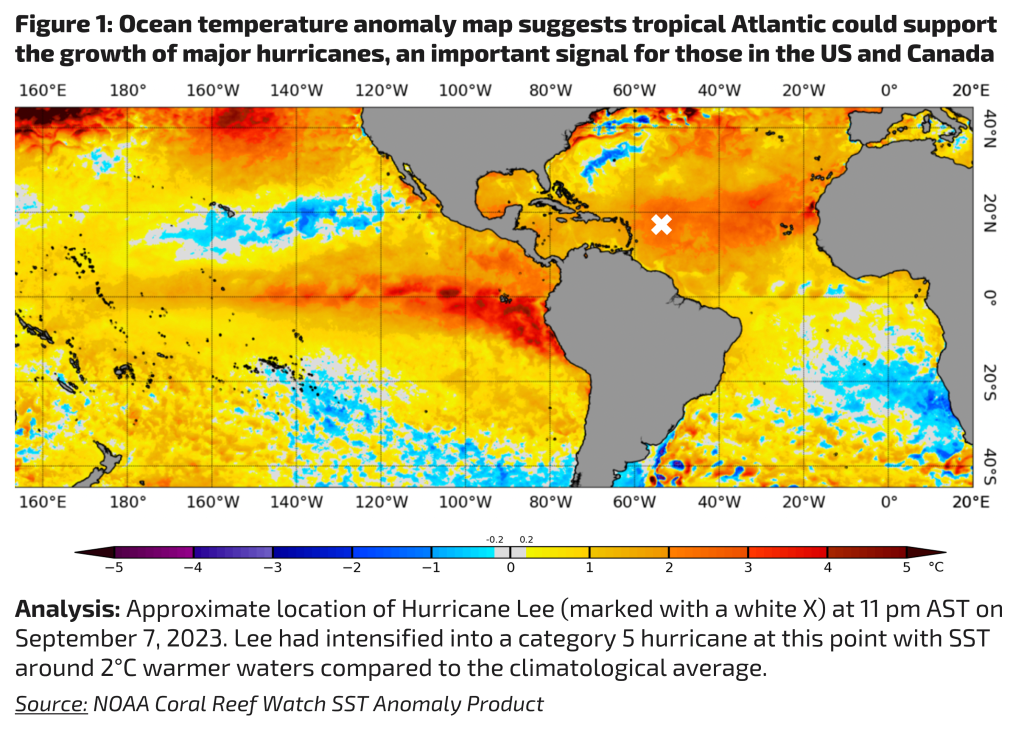

How did Lee make such an astonishing jump in just 1 day? The answer lies in the surrounding atmosphere and ocean. The atmospheric conditions around Lee – mainly lack of wind shear – were extremely conducive to the storm’s intensification. Wind shear can prevent a hurricane from growing, or even altogether destroy it if a system is in its infancy. More importantly, on the oceanic side of the equation, the factor that drove Lee’s rapid escalation was the abundance of available fuel, which for hurricanes is simply warm ocean water. The tropical Atlantic around Lee was anomalously warm, as illustrated in figure 1.

Following the extreme 24 hour jump in Lee’s intensity, the sky was the limit as for how powerful the storm could become. Lee was on pace to become one of the strongest hurricanes ever recorded in the Atlantic basin. Fortunately, this did not end up being the case – a hostile atmosphere weakened Lee into a category 3 storm, albeit still a major hurricane

Lee’s swift progression from a category 1 to 5 storm raises an essential question that is in our best interest to answer amid the rising frequency of such storms. How likely is this scenario to repeat in the future?

According to NOAA, the world’s oceans absorb 90% of excess heat from anthropogenic warming (Lindsey & Dahlman). Although there are many factors that influence hurricanes, warmer oceans generally translate to a higher likelihood of storms intensifying into major hurricanes. A greater frequency of major hurricanes in the Atlantic increases the potential that adjacent countries will experience severe impacts. From 1924 to present, there were 40 category 5 hurricanes. Of these 40 storms, 20% came in the last decade and 40% came in the last two decades (Erdman). It is incumbent upon decisionmakers to observe this upward trend for planning and resilience efforts as category 5 storms potentially make landfall with greater regularity.

It is also imperative to monitor the greenhouse gases that are contributing to this problem. Floodlight’s SAGE product is a piece to this puzzle, providing directly measured carbon emissions data that can serve as a key input to climate change mitigation efforts. SAGE is fully dynamic, serving as a useful tool for stakeholders across both the public and private sectors.

For more information on SAGE and the rest of our offering, please visit our product page or feel free to reach out to us directly.

Citations:

Erdman, J. (2023, September 10). Category 5 hurricane history in the Atlantic Basin. The Weather Channel. https://weather.com/safety/hurricane/news/2023-09-07-category-5-hurricanes-atlantic-history

Hurricane Lee Discussion Number 7 . (2023, September 6). Retrieved September 12, 2023,.

Hurricane Lee Discussion Number 11. (2023, September 7). Retrieved September 12, 2023,.

Lindsey, R., & Dahlman, L. (2023, September 6). Climate change: Ocean heat content. NOAA Climate.gov. https://www.climate.gov/news-features/understanding-climate/climate-change-ocean-heat-content

NOAA Coral Reef Watch Daily 5km satellite coral bleaching heat stress SST anomaly product (version 3.1). (2023, September 7). https://coralreefwatch.noaa.gov/product/5km/index_5km_ssta.php