Key Takeaways

- The EU’s CBAM regulation imposes a carbon tariff on imports. It seeks to level the playing field for domestic producers already subject to reporting and paying for their emissions.

- The tariff results in domestic and foreign producers paying the same for the carbon content in their products. Noncompliance with the regulation comes with steep financial penalties. Foreign producers can mitigate these costs through diligent emissions reporting and related payment.

- Foreign producers can adapt to CBAM by readying themselves to quantify and report their carbon emissions. We believe our direct GHG emissions measurement solutions provide companies with the science-backed data and regulatory readiness needed to succeed in today’s fast-moving legislative environment.

The EU’s carbon-reduction regulations are the world’s most ambitious and intensive to date. Over the past few years, sustainability aspirations evolved into meaningful action and change – Europe is successfully developing comprehensive sustainability disclosure requirements and facilitating private sector decarbonization by charging companies for their carbon emissions. Such changes, though, come with growing pains. On top of the direct costs of their emissions, in-scope businesses must also grapple with allocating capital to decarbonize production practices and to build out sustainability reporting infrastructure. The burden of these expenses ultimately falls on their bottom lines. Many businesses fear that this put them at a competitive disadvantage compared to their less regulated peers in the United States and China. Fortunately, recent legislative developments can quell some of these worries.

Adopted in 2023, the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) introduces new costs for carbon emitted in the production of goods that enter the EU. The regulation seeks to ensure that the cost of carbon from imports is at parity with that of domestically produced products after adjusting any costs which may already be present in the exporting country. The intended impact is simple. Regulators hope to level the playing field for European operators by disincentivizing outsourcing to markets with less stringent emissions rules and by making EU products more cost competitive. And of course, they hope to do this while furthering the bloc’s climate change mitigation ambitions.

In practice, CBAM levies a tariff on imported goods based on their carbon content, requiring importers to purchase quantities of CBAM certificates that correspond to the reported emissions of their EU-bound products. These certificates are priced weekly at auction, based on the average price of EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) allowances. In the current rollout phase, the regulation only applies to select carbon-intensive sectors: cement, iron and steel, aluminum, fertilizers, electricity and hydrogen. Foreign producers’ sole obligation during this time is to report the scope 1 and 2 attributed to their exports to the EU. In 2026, the tariff component of the rule kicks in, with importers paying for their emissions per the method described above.

Whether CBAM will deliver on its intended impact depends on importers ability to fulfill their obligations, and relatedly, how trade partners respond to the new requirements. Addressing the former, the penalty regime included in the regulation introduces meaningful financial measures to disincentivize noncompliance. It initially charges up to €50 per tonne of unreported emissions, with larger penalties imposed for repeated noncompliance. On top of this, many EU member states plan to issue their own penalties for noncompliance.

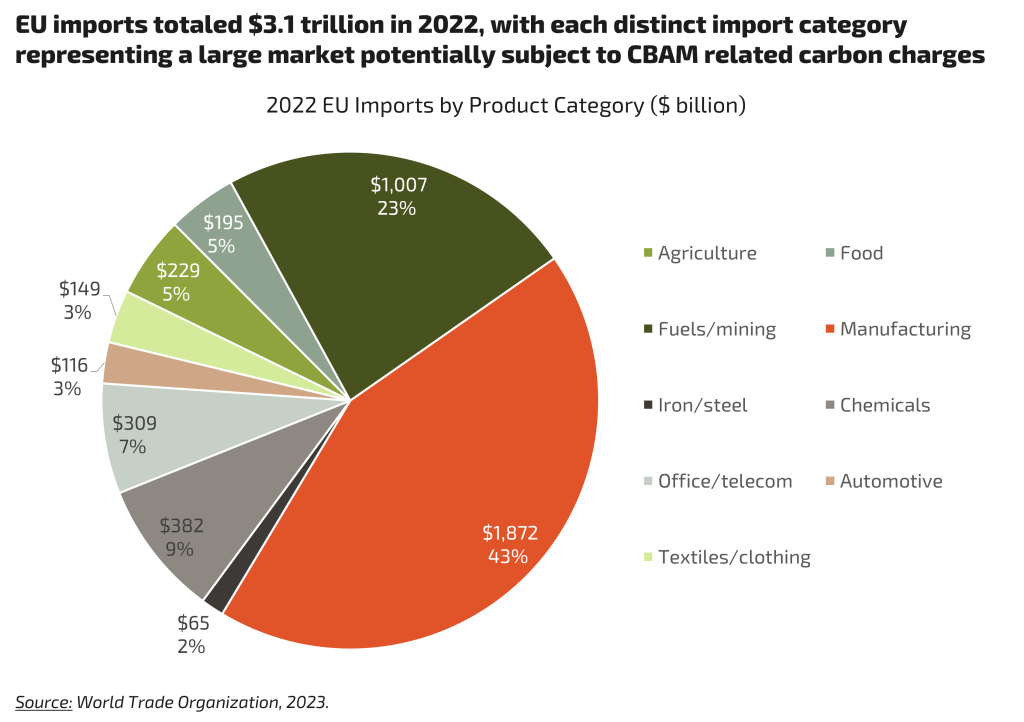

In our view, it is comply or die for foreign producers. As a bloc, the EU was responsible for $3.1 trillion of imports in 2022, representing over 10% of all global imports and ranking only behind the United States.1 Avoiding the European market to escape its regulatory environment is simply not an option. And given CBAM’s steep penalties, nor is noncompliance. So, how can foreign producers adapt? We believe much of the solution lies in how companies quantify and report their emissions, as well as their readiness to do so.

Traditional carbon reporting methods do no favors for companies seeking to be nimble around regulations like CBAM. They rely on imprecise estimates, capital intensive internal infrastructure, and costly external data providers, as well as being inordinately time consuming and not achieving the gold standard of reasonable assurance. With regulations becoming increasingly stringent, companies must constantly evolve their carbon accounting practices, underscoring and perpetuating these negative characteristics.

Floodlight’s direct GHG emissions measurement solutions, on the other hand, provide companies with the science-backed data and regulatory readiness needed to succeed in today’s fast-moving legislative environment. Using satellites and sensors, Floodlight delivers high-precision emissions data for any location on the planet. This is done fully remotely, offering reasonably assured data in just a matter of days and at a fraction of the cost of traditional carbon accounting methods. In our view, companies looking to their CBAM obligations should look no further.

References

- World Trade Organization, 2023.